New Caledonian Politics

by W.S. McCallum © 1993, 1998

1. New Caledonia 1878: The Kanak Insurrection

2. The FLNKS in New Caledonia 1984-1994. From Violence to Cooperation with the French State

3. New Caledonia 1998: le retour aux sources

1. New Caledonia 1878: The Kanak Insurrection

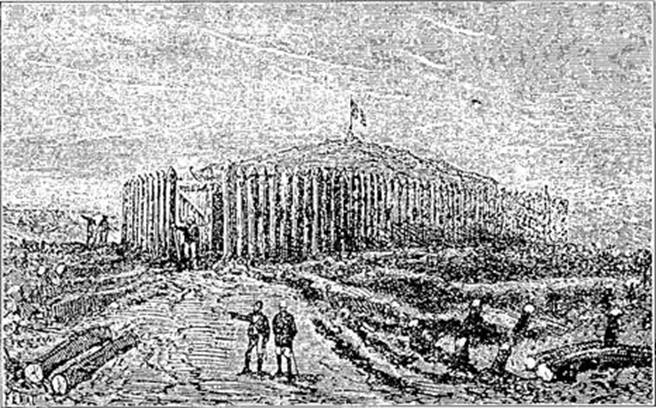

La Foa blockhouse

Background

New Caledonia became a French territory on 24 September 1853, when Rear-Admiral Febvrier-Despointes claimed the archipelago. Situated in the South-West Pacific at the northern end of the Tasman Sea, New Caledonia had been the scene of rivalry between French Marist and English Protestant missionaries, and it was deemed timely to claim the isles before perfidious Albion did so.

French settlement in New Caledonia proceeded irregularly. The colony's isolation and tales of cannibals deterred many a prospective settler, while crop failures due to drought, pestilence or poor soil sent many settlers who did reach New Caledonia heading elsewhere. France's decision to use New Caledonia as a penal colony from 1864 also did little for the islands' image. Despite setbacks however, French settlement made inroads on the Grande Terre or mainland. By 1878, over 13,000 Europeans were living in New Caledonia, along with around 1,200 African, Asian and Pacific Islander labourers.

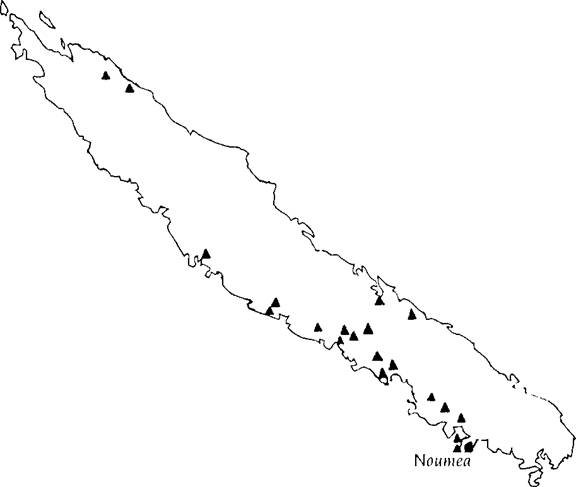

▲ Military post, 1878

The Grande Terre of New Caledonia

The islands' Melanesian inhabitants, nowadays called Kanaks, lived in dozens of tribes scattered around the colony. The Kanaks had welcomed the earliest European settlers but conflict was inevitable as those tribes in contact with the French realised that not only did these strange visitors intend to stay permanently, but they also desired to occupy tribal land to establish farms and settlements. As French settlements spread along the west coast, recurrent massacres occurred. Isolated settler families were periodically murdered and eaten, provoking swift crackdowns from the colonial government, which would despatch gendarmes and/or troops to take reprisals.

In the 1870s, the situation worsened for those tribes living in the centre of the Grande Terre. They had already witnessed the decimation of southern tribes at the hands of the French in 1859, and realised that unscrupulous settler land grabs were also beginning to threaten their existence. Tribes forced off prime agricultural land by settlers were pushed up mountain valleys along the Grande Terre's central mountain chain, leaving them with barren land on which to try to cultivate their crops. Another threat to Kanak well-being came from wandering cattle introduced by the French. Settlers seldom fenced off their herds. These caused havoc, trampling and eating tribal crops which occasionally left tribes short of food. By 1878, there were 80,000 cattle in New Caledonia, compared to an estimated Kanak population of 70,000. Repeated complaints to the colonial administration brought no lasting solution to Kanak grievances. Consequently, a group of tribal leaders took the unprecedented step of forming a large-scale inter-tribal alliance to plan a decisive strike that would force the French back.

Theatre of Operations, 1878

The Insurrection

The incident that sparked the insurrection occurred from 18 June 1878. On the west coast of the Grande Terre, 22km north-west of Bouloupari, a settler was murdered, along with his Kanak wife and their child. The massacre had been carried out by members of two local tribes. The Bouloupari and La Foa gendarmes investigated, and arrested eight local chiefs and seven warriors. The chiefs remained imprisoned at the gendarmeries of La Foa and Bouloupari, where they were to languish for only a few days...

With so many chiefs simultaneously in the custody of the French, the insurrectionists decided to act. The main force behind the insurrection at this stage were two powerful local tribes - the Dogny, and the Uarai. Atai, the leader of the Uarai, was to become the most infamous of the insurrectionists. At 5am on 25 June, their warriors surrounded the gendarmerie at La Foa and attacked. They achieved complete surprise, and freed those tribesmen held prisoner after killing the gendarmes. At almost the same time, colonists were attacked around Dogny, La Fonwhari and La Foa.

Word of the attacks reached Lieutenant Vanauld, commander of the coastal garrison of Teremba, by 8am. He alerted the capitol, Nouméa, and set about investigating. Seven marines were sent off in a penitentiary carriage to reconnoitre La Foa, while Vanauld followed with 16 marines, leaving behind 16 men to hold Teremba. On the way to La Foa, Vanauld received a message from his reconnaissance force that the massacres were part of a general rebellion. He also received a disturbing message from Teremba - the garrison was under attack. At La Foa, Vanauld left behind 12 men to evacuate survivors, while the marines in the carriage travelled further afield to alert isolated homesteads.

Vanauld hurried back to Teremba with six men, determined that the post should hold. Chief Atai had attacked the post with a large force and set a nearby brickworks on fire. When Vanauld returned around 11.30am, Teremba was virtually surrounded. Relief was close at hand. The gunboat La Vire was expected by Vanauld, as it was making a survey trip around New Caledonia. The ship arrived in the bay around 1.00pm. La Vire's commander, Captain Rivière, had four cannons at his disposal and, when he sent a landing party ashore, Atai's force withdrew. Teremba was now secure, and Rivière detailed some of his sailors to assist Vanauld in finding settlers to evacuate.

On the morning of 26 June, a group of around 300 warriors from the Ouaménie, Gwi and Koa tribes went on the war path. After some general pillaging, at 10am they attacked the gendarmerie at Bouloupari. Three gendarmes were killed, one escaped, and one was wounded but was later rescued. The imprisoned Kanak chiefs languishing in the cells were released. The war party also murdered Bouloupari's telegraph operators and their families, and ransacked the telegraph office. Following this, they attacked the prison camp at Bouloupari, killing 26 prisoners and two overseers. Only three prisoners and the camp commandant escaped.

Some help was at hand. Lieutenant-Colonel Galli-Passebosc, New Caledonia's military commander, in an attempt to find out what was happening around La Foa and Bouloupari, had rushed to the area aboard the vessel La Seudre with 200 troops and disembarked three squads of marines at Bouraké, 18km from Bouloupari. This detachment never reached Bouloupari, as it was forced to turn back after being surrounded by a group of insurgents. However, it did succeed in rallying fleeing colonists, who were later evacuated by ship to Nouméa. Galli-Passebosc had, in the meantime, moved on to Teremba, to consult with Rivière. It was only on the evening of 26 June that he learnt of the massacre at Bouloupari, and a report of what had happened to his detachment.

As a result of the attacks on La Foa and Bouloupari, two gendarmeries had been destroyed, over 100 colonists were dead, and many more were wounded. Homesteads and settlements had been ransacked and burnt. News of the events in Nouméa that day provoked panic. Rumours circulated of impending attacks by the southern tribes on Nouméa, although none eventuated. Governor Olry stayed calm, but did order the evacuation of other convict camps near the danger area, declared a state of siege, and raised a volunteer unit of horsemen to supplement the troops already in the colony. As an added precaution, Kanaks resident in Nouméa were interned.

The French response to the insurrection was to organise columns to occupy the Bouloupari/La Foa area. Efforts were also made to rally tribes traditionally hostile to chief Atai and his allies. On the east coast, on 27 June, the French district officer at Canala rallied over 400 warriors of the Canala tribes to the French cause, whom he led over the mountain, to the La Foa region. Later, the Bourindi from Thio joined the French, as did tribes from Paita. Both La Foa and Bouloupari were reoccupied by early July, but the surrounding areas were far from subdued, so plans were made to re-establish communication links through the region, build blockhouses, and subdue the insurgents with mobile columns. Faced with difficult terrain, and an enemy with superior speed, better bushcraft, and an intimate knowledge of the terrain, the French experienced mixed results. On 3 July, while his column had stopped near La Foa to repair cut telegraph lines, Galli-Passebosc was fired on by Kanak snipers and was gravely wounded. Two days later, he died from his wounds. The snipers escaped from the scene.

Rivière took over as New Caledonia's military commander, and resolved to continue Galli-Passebosc's pacification plans. Kanak resistance was still heavy though. Just days after Rivière took over command, 500 warriors attacked Bouloupari, who were fought off by its garrison of some 100 sailors. On 8 July, a column marching on Bouloupari from Paita was surrounded by 300 warriors. Rivière sent off a relief force from Bouloupari and successfully disengaged the column. During July, the French and Kanaks burnt each others' villages in reprisals, but neither side could claim any conclusive victory in the field.

In August, the insurgents made repeated attempts to overcome the garrison of La Foa; some 80 men under a Captain Lafond. While in the middle of constructing a blockhouse, Lafond's men were attacked on 13 and 18 August. Both attacks were repelled. Just as the blockhouse was completed on 24 August, around 500 warriors attacked. They suffered heavy losses, including chief Morai of the Ourail tribe, who probably commanded the force. The defenders suffered only two men seriously wounded, and several had light wounds. Two days later, a column was sent off to track down the fleeing insurgents, but it found itself encircled, and the French had to withdraw.

The French hope that the insurrection would remain isolated to the La Foa/Bouloupari area was in vain. Tribes to the north-west also rose. On 21 August, the Moindou tribes joined the insurrection, then the Poyasées on 11 September, followed by the Guaro, Nera and Nessadiou on 24 September and, at the beginning of October the rest of the Bourail tribes and the large tribes near Koné. Rivière concentrated his efforts on the original insurgents. On 1 September, Rivière sent three columns off from La Foa to drive Atai and his allies into three other columns set up to cut off lines of retreat. Around noon, Atai was surprised in his camp by one of the columns. Most of his warriors fled, and he was speared by a Canala warrior before he could use a gendarme's sabre that he was equipped with. He and six other warriors were beheaded. Atai's death was a major blow, but it did not stop the insurgents. Atai was not their only capable leader.

The French concentrated on systematically raiding and burning Kanak villages. These attacks netted many women and children, who were handed over to friendly tribes as prizes of war. Nonetheless, by the end of September, the insurrection, despite French efforts at containment, had spilled over into a larger area, causing more massacres of colonists, and more rushed evacuations to Nouméa. But, however slowly, the French were gaining control. Rivière split his command, concentrating his efforts south east of Bourail, while delegating command of forces north-west of Bourail to one Lieutenant-Colonel Wendling. French reinforcements arrived, in the form of further troops, and tribes which had decided it was advantageous to join the French side. Around Koné, the tribes went over to the French, and the Houailou tribes of the east coast crossed the mountains, wreaking havoc around Bourail.

By the end of October, the French had succeeded in setting a cordon up around insurgent tribes, and held the initiative. They had, by now, forced their opponents from their villages, and into various refuges, where they were forced to rely on whatever provisions they might have. The Kanaks took advantage of the rugged terrain of the central mountain chain, hiding in caves and other remote spots. One limestone formation, dubbed ''the fortress of Adis'', was held by insurgents from October through to 21 November. The Kanaks held out against repeated attacks, finally withdrawing when their position became untenable.

In December, faced with continued French raids and attacks, insurgent tribes began defecting to the French. For all this, the insurgents were far from beaten, but the end was now in sight. Fighting continued until April 1879, but by 18 April, Governor Olry was able to write to his superiors that, effectively, the insurrection had been quelled. The cost had been high for such a small colony: over 200 European settlers were dead, and over 200 farms had been pillaged and destroyed. Among the insurgents, it was estimated some 1,200 had died in combat, with uncountable non-combatants abducted by tribes allied to the French. 600 insurgents were deported to the isle of Pines, and 200 to the Belep Isles. Those prisoners assumed to be more dangerous were deported to distant Tahiti.

Weapons and Tactics

For the French, the New Caledonian insurrection of 1878 came as a great surprise, and as an immense shock. Racist stereotypes of the times portrayed the Kanaks as stupid, lazy, and cowardly. The degree of planning that went into the insurrection, and the skill with which the insurgents fought, outgunned and outnumbered, shook these assumptions.

Despite over a century of European contact, the typical Kanak warrior of the 1870s had not changed greatly from pre-European times. Traditional weapons such as spears, stone axes and slingshots were the main arms. The Kanaks used bows, but only for hunting and sport. The appearance of Kanak warriors varied from tribe to tribe, but typical garb consisted of either a loincloth, penis gourd, or skirt (grass or fabric), body paint, and head dress of varying descriptions. Some tribes also wore anklets. Turbans were quite common, but bore little resemblance to the Indian variety.

Paradoxically, those tribes allied to the French were generally less Europeanised than the insurgents themselves, who wore items of European clothing, including caps, trousers, shirts and jackets in addition to more traditional dress. Chief Atai was described as wearing an infantryman's trousers and képi, a military jacket with gold epaulettes and, as mentioned previously, carried a captured sabre. Such dress would have been less prevalent among the rank and file of his followers. The insurgents also widely used European iron hatchets or tamiocs, superior to traditional stone axes (which were called gi). It is difficult to quantify the number of firearms used by the insurgents, but they were not abundant. Those riflemen that the insurgents possessed however, were competent shooters. The insurgents, both before and during the insurrection, made concerted attempts to obtain firearms. Seasonal workers on European properties purchased guns and ammunition with their wages. Scrap metal was also melted down into shot to save on the cost of purchasing ammunition. Numbers of firearms were also netted in assaults on homesteads, settlements and gendarmeries. Types of guns used therefore included a mix of civilian types, both muzzle loaders and breech loaders. Also present, no doubt in smaller numbers, were captured examples of the military Chassepot, the standard service rifle with French troops in New Caledonia from 1869. The insurgents possessed no artillery.

Traditionally, the Kanaks of New Caledonia relied on stealth and surprise in their tribal wars. Massed, open battles between tribes were rare. Instead, tribal warfare consisted of a series of ambushes and raids on villages, reprisal following reprisal. Engagements usually ended after one side had lost only three or four warriors, so that their bodies might be evacuated safely from the field. To have your dead captured, dismembered and/or eaten by a hostile tribe was considered shameful. This habit persisted in the insurrection of 1878. The Kanak custom of removing their dead from the battlefield made it difficult for the French to gauge the effectiveness of their shooting.

True to their traditional style of warfare, and also prompted by an awareness of French firepower, the insurgents avoided open confrontation with French columns. Warriors would harass columns with thrown spears, slingshots, and the occasional gunfire, while taking advantage of the dense cover that the New Caledonian bush offered. Attacks on columns usually involved skirmishers assaulting the flanks and rear.

Different tactics were adopted in 1878 for assaults on military posts and French settlements. Warriors would attack in three waves. The first consisted of the spearhead; the second was assigned to gathering plunder (French clothes, guns, supplies, tools or anything else deemed useful); and the third torched buildings before the force withdrew. The insurgents were also well aware of the value of telegraph lines, and would cut these wherever possible to avoid word of attacks reaching further afield. Unlike, for example, the Zulus, the Kanaks generally would not press home an attack when faced with overwhelming firepower aimed across open ground. Some contemporary observers saw this as proof of cowardice. More likely, it was the result of common sense.

Wherever possible, the insurgents chose not to be pinned down by French troops, as this would inevitably result in heavy losses and probable defeat. They were nonetheless aware of the possibilities offered by fortified positions. Traditionally, Kanaks limited the approaches to the narrow valleys in which hill tribes lived by planting hedges, barriers of banyan groves, or by constructing walls with piled stones. Natural citadels such as limestone caves and rock formations were also used in defence.

French troops involved in the insurrection of 1878 went into battle with much the same arms and uniforms as used in the Franco-Prussian War. Few concessions seem to have been made to the local climate, which is very humid, and stays above 20°C even in mid ''winter''. Photos taken of French troops based in New Caledonia in the 1870s show them wearing the same heavy greatcoats as were used in France. Tropical white trousers and shirts were used, along with blue jackets and greatcoats. Headdress consisted of white pith helmets and the ubiquitous blue képi.

French irregulars were a mixed bag. ''Convict soldier'' units were raised from the various penitentiaries on the Grande Terre, and had a reputation of lawlessness and brutality. Being lightly equipped, they were used as scouts. These men were under the command of a warder named Mercury, and were nicknamed les Mercury.

Also present on New Caledonia were large numbers of political prisoners, notably supporters and leaders of the Paris Commune who had been deported. Interestingly, many Communards volunteered to fight in support of the French institutions they had violently opposed only a few years before. The first unit, of 36 men, was raised shortly after the insurrection began. They were led by their own democratically-elected officer, a Lieutenant Malherbe. Equipped, like other French troops, with Chassepot rifles, the Communards were used as franc-tireurs, and fought lightly clothed, often in shirtsleeves. A second unit of Communards, also of 36 men, went into action in November 1878, led by the overseer Bonnieux. Mention should also be made of volunteer horsemen, raised from free colonists.

Neither should the contribution made by friendly tribes be neglected. It has been argued that, without the help of these warriors, the French campaign would have foundered. Tribesman were used as flying columns, travelling faster than the French columns. Due to their speed and better knowledge of terrain, these tribesman frequently operated independently of the French columns.

French columns aimed to be mobile, and were not as big as might be thought. For example, the three mobile columns which were the centrepiece of Rivière's operation on 1 September 1878, (which resulted in the killing of chief Atai), consisted of the following. The right column contained 18 franc-tireurs, 12 Mercurys and 30 tribesmen. The left column had 35 soldiers, five franc-tireurs, five Mercurys, and 500 Canala warriors. The centre column had 25 soldiers, five franc-tireurs, five Mercurys, and 20 Canala warriors.

The French response to the insurgents was to wage a war of attrition, a strategy that the Kanaks were ultimately unable to counter. The widespread destruction of Kanak villages and crops, along with the abduction or slaughter of women and children eventually deprived the Kanaks of their logistical support. This, combined with the overwhelming numbers of troops the French fielded, caused grave problems for the Kanaks. In the first few days of the insurrection, the insurgents enjoyed a numerical advantage over isolated posts and settlements around La Foa and Bouloupari, having an estimated force of several hundred warriors. But the French soon deployed some 2,500 French regular troops and many more irregulars. By the end of the campaign, the French had 4,665 regulars in the field, although many of these were spread out guarding posts and supply lines. Despite their overwhelming superiority in arms, numbers, and logistical support, the Kanaks gave the French a difficult time, using guerrilla tactics involving the massing of forces against weak points such as supply columns and isolated garrisons.

References

Bronwen Douglas: ''“Almost constantly at war”? An ethnographic perspective on fighting in New Caledonia'' in The Journal of Pacific History vo1. 25 no. 1 1990.

Roselene Dousset-Leenhardt: Colonialisme et contradictions: Nouvelle-Calédonie 1878-1978. L'Harmattan, Paris, 1978.

Roselene Dousset-Leenhardt: Terre natale. Terre d'exil. G.P. Maisonneuve et Larose, Paris, 1976.

Patrick O'Reilly: Photographies de Nouvelle-Caledonie. Nouvelles Éditions Latines, Paris, 1978.

Jean-Marie Tjibaou et al.: Kanaké - the Melanesian Way. Les Éditions du Pacifique, Papeete, French Polynesia, 1978.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum December 1993

2. The FLNKS in New Caledonia 1984-1994.

From

Violence to Cooperation with the French State

The Matignon Accords, 26 June 1988: Jacques Lafleur (RPCR) and Jean-Marie Tjibaou (FLNKS).

(Haut-Commissariat de la République en Nouvelle-Calédonie)

The Political Landscape

The 1980s represented one of the most violent periods of New Caledonia's history since its annexation by France in 1853. Over fifty people were killed in sporadic confrontations, mainly from 1984 to 1988, over the question of territorial independence. From September 1984, the Front de Libération Nationale Kanake et Socialiste (National Kanak Socialist Liberation Front-FLNKS), the largest Melanesian nationalist formation in New Caledonia, campaigned for Kanak sovereignty. Roadblocks, bombings, riots and shootings appeared to have become commonplace by the final weeks of 1984. French loyalists opposed to independence railed against, and Kanak nationalists prophesied, the supposedly imminent foundation of an independent Republic of Kanaky. Yet Kanak discontent with French sovereignty failed to lead to conflict on the same scale as the tribal rebellions of 1878 and 1917 when, respectively, around 1400 (Dousset-Leenhardt 1976, 168) and 220 people (Raluy 1990, 85) had been killed. In 1984 French journalists and politicians declared rhetorically, and erroneously, that developments in New Caledonia were becoming a rerun of the decolonisation of French Algeria. However a decade later France still exercised sovereignty over New Caledonia, the Republic of Kanaky remained an abstract concept rather than a recognised state, politically-motivated violence played no part in territorial life, and the followers of Kanak nationalism and French loyalism were coexisting peacefully.

Although since 1984 the most powerful expression of Kanak demands has been the FLNKS, this coalition has attracted inadequate electoral backing to gain independence through the ballot box. Under the Constitution of the French Fifth Republic, Paris may grant independence to one of its overseas territories only if an absolute majority of the territory in question has expressed support for secession from France in a self-determination referendum. It was under this constitutional framework that the Comoros, in 1975, and Djibouti, in 1977, gained their independence after voting for self-government.

In New Caledonia, there exists no majority support for independence. Unlike the Melanesians of Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, New Caledonia's indigenous inhabitants have become an ethnic minority in their own lands, representing 44.8 per cent of the local population in 1989. The immigrant groups which have settled in New Caledonia since French annexation of the islands in 1853 not only enjoy an absolute majority of the territory's population, but also of its electorate. These immigrants and their descendants, concentrated predominantly in the south of the Grande Terre, the New Caledonian mainland, have opposed Kanak nationalism as a threat to their future in the territory and have consistently voted for conservative parties advocating continued links with France. For example, in the French legislative elections of March 1993, of the 54,411 voters who participated in New Caledonia, in total 11,545, or 21.22 percent, voted for the two FLNKS candidates. The two candidates presented by the Rassemblement Pour la Calédonie dans la République (Assembly For Caledonia in the Republic-RPCR), the largest French loyalist party in the territory, received a total of 28,255 votes, or 51.93 per cent of the territorial vote.

Much coverage of the contemporary political situation in New Caledonia in the English language South Pacific press, (for example the writings of Helen Fraser and David Robie in Pacific Islands Monthly) has tended to neglect such primary constitutional, demographic and electoral considerations. It has been tacitly assumed that the French State has a moral obligation to unilaterally grant independence in response to the FLNKS's claim to represent the original inhabitants of New Caledonia, its Melanesians. Such inherently pro-Kanak analysis was also voiced by various South Pacific politicians in the 1980s. For instance in January 1982 Bill Hayden, who was appointed foreign minister for the Australian Labor Government from 1983, declared that France should preferably grant New Caledonian independence within five years (SMH, 7 January 1982). He dismissed the absence of majority support for secession in the territory as irrelevant, expressing the claim that Kanak sovereignty was effectively an historical inevitability, as by the late 1980s Melanesians would have the status of a territorial electoral and demographic majority. History has proven otherwise. Certain less impassioned academic commentators have also made the elementary error of misinterpreting the constitutional framework for New Caledonian independence. For example Robert Aldrich has written that Paris might have unilaterally granted independence to New Caledonia in the 1980s (Aldrich 1993, 266), although this was not possible without major constitutional reforms and was not a politically admissible option for any administration of the day. For better or worse French governments under the Fifth Republic, whether leftist or centre-right, have generally worked within existing constitutional structures to promote reform in New Caledonia. The major barriers to successfully granting independence to an electoral and demographic minority in New Caledonia should not be overlooked. It was singularly unlikely in the 1980s that, in the highly improbable event of a French government being prepared to alter the constitution to unilaterally grant independence to the territory, civil order would have been maintained there. Regardless of moral considerations, New Caledonia's non-indigenous population was no more prepared to passively contemplate sovereignty being granted to a Kanak minority than non-indigenous populations would have been to abdicate sovereignty in the face of minority indigenous nationalist movements in Australia, New Zealand, or Hawaii.

Bearing constitutional, demographic and electoral considerations in mind, this essay examines why the FLNKS, after ten years of activism, was still no closer to gaining Kanak independence than it was at the time of its foundation. It is also explained why, contrary to the predictions of various observers in 1984, the national liberation struggle proclaimed by the FLNKS did not develop into a campaign of guerilla warfare against the French presence. Examination is offered of the material limitations which rendered the formation ill-prepared to convert its revolutionary rhetoric into concerted armed struggle. Then the course of the two FLNKS militant campaigns to date, those of 1984 and 1988, is charted to illustrate how these limitations were reflected in the coalition's use of political violence. It is also argued that the limited and harmful effects of this violence led the FLNKS to tone down its militant agenda and agree to pragmatic collaboration with the French State, in the hope that Kanak independence might be attained by peaceful means.

This article avoids arguing a moral case for or against the concept of Kanak sovereignty, as too much published writing on contemporary New Caledonian politics has been deleteriously influenced by partisan political viewpoints. Certain conservative French commentators (Desjardins 1985, ARLR 1985) dismissively berate the FLNKS as savage terrorists, heralding a return to barbaric primitivism in New Caledonia. Such argumentation is as overstated as that of certain pro-Kanak French writers (Coulon 1985, Gabriel & Kermel 1985), who have placed a strident leftist anticolonialist gloss on FLNKS activism which the movement has been largely incapable of and, since 1988, somewhat uninterested in pursuing. While avoiding polemicising, attention is devoted below to the limitations, accomplishments, and implications of FLNKS activism in New Caledonia.

The Limitations of Violence

The foundation of the FLNKS on 24 September 1984 marked the beginning of a period of more forceful Kanak radicalism that broke, although not durably, with the participation in French democratic institutions of its predecessor, the Front Indépendantiste (Independence Front). Lacking the support of a majority of the territorial electorate, for the advancement of its nationalist goals the FLNKS has wavered between pragmatic participation and sometimes violent disruption of the French democratic system.

A new territorial statute promulgated in September 1984 (JO, 1984), and named after Georges Lemoine, then Secretary of State to Overseas Departments and Territories, had failed to live up to Kanak demands. These demands involved immediate independence through a self-determination referendum restricted largely to voters from the indigenous minority of the local population. Instead, the Lemoine Statute offered a referendum for 1989, to be conducted according to French constitutional law, which required the support of an absolute majority of the local electorate before independence could be granted by the French State. Eligible voters would be able to participate regardless of their ethnic origin. Accusing the Socialist Government of being in league with the forces of colonialism in New Caledonia, the FLNKS broke off dialogue with it and called on Kanaks to organise "the conquest of liberty" (FLNKS 1987, 7). In its charter (FLNKS 1987, 6), the formation proclaimed a national liberation struggle. Struggle committees were organised, intended to be at the forefront of Kanak opposition to French rule. They were instructed to conduct "political actions of destabilisation of colonial and neo-colonial interests" (FLNKS 1987, 37).

In its resort to violence, the FLNKS faced a lack of resources which set it apart from the Algerian and Vietnamese national liberation movements of the 1950s. The support base that the FLNKS claimed, New Caledonia's indigenous Melanesian population, was less imposing than the millions from whom the Front de Libération Nationale (National Liberation Front-FLN) and the Viet Minh drew their support. The nationalist agenda of the FLNKS was in addition hindered by the culturally segmented, undeveloped nature of the indigenous population in New Caledonia.

Indigenous Melanesians constituted 42.56 per cent of the territorial population in 1983; 61,870 people out of a total of 145,368 inhabitants (INSEE 1984, 61). Of the 61,870 indigenous Melanesians recorded at that time, 42 per cent were under the age of 15 (INSEE 1984, 62). In spite of being habitually referred to by the FLNKS as "the Kanak people", indigenous Melanesians were in fact far from constituting a homogeneous group. They belonged to 319 tribes (Tjibaou & Missotte 1978, 117-118), speaking between them twenty-seven different languages. Supporters of the FLNKS tended to be found in the least-developed parts of New Caledonia. In 1983, 73 per cent of indigenous Melanesians (INSEE 1984, 61) lived in tribal societies in the rural hinterland, which relied on collective, subsistence agriculture, supplemented by cash proceeds from seasonal labour. These communities offered an unpromising foundation for the socialist nation-state heralded by the FLNKS.

Melanesian political divisions represented another challenge to the concept of a unified Kanak people. The FLNKS itself was an electoral coalition of five parties, three lobby groups and a trade union. At its foundation, the most prominent member party was the Union Calédonienne (Caledonian Union-UC), the component with the largest following. Alongside the UC stood various minor political parties: Parti de Libération Kanake (Kanak Liberation Party-Palika), Front Uni de Libération Kanake United Kanak Liberation Front-FULK), Union Progressiste Mélanésienne (Melanesian Progressive Union), and the Parti Socialiste de Kanaky (Socialist Party of Kanaky). The lobby groups were the Comité des terres de la côte ouest (West Coast Land Committee), Comité Pierre Declercq (Pierre Declercq Committee), and the Groupe des femmes kanakes et exploitées en lutte (Group of Exploited, Struggling Kanak Women). The sole trade union member was the Union des Syndicats des Travailleurs Kanaks et Exploités (Syndical Union of Exploited Kanak Workers-USTKE). While a large majority of indigenous Melanesian voters backed the concept of Kanak sovereignty, not all of them supported the FLNKS. Libération Kanake Socialiste (Kanak Socialist Liberation-LKS) is a minor nationalist party which has rejected the FLNKS's claim to represent the Kanak people.

Still other Melanesians, estimated in 1985 to constitute around 20 per cent of indigenous voters (Le Monde, 3 October 1985), rejected Kanak nationalism in preference to French loyalist parties. Melanesian loyalists voted with the non-indigenous electoral majority in New Caledonia. Since the foundation of the FLNKS, French loyalists, whether of Melanesian, Polynesian, Asian or European origin, have repeatedly accorded the RPCR an absolute majority of seats in the Territorial Congress, the local parliament. The RPCR was created by a mix of conservative groups and individuals. Of New Caledonia's parties it has the largest electoral following. It has close ties with the metropolitan French Rassemblement Pour la République (Assembly For the Republic-RPR), the latest incarnation in a long line of French Gaullist political parties, but is an independent formation. Although the RPCR's three representatives in the French Parliament (two deputies and a senator) sit on the RPR benches, they have differed with the RPR over some aspects of New Caledonian policy. French loyalist electoral predominance has frustrated Kanak hopes of gaining independence via the ballot box.

Frustration at its inability to erode loyalist electoral dominance was the reason why the FLNKS decided to boycott the territorial elections in 1984. But drawn from largely rural support among a population of under 62,000 indigenous Melanesians, the formation controlled insubstantial human resources for its national liberation struggle. Although no statistics exist concerning the number of FLNKS activists who participated in militant protests, in 1984 and in 1988 probably no more than several hundred Kanaks operated at the sharp end of conflict. These militants tended not to be very well armed. Many of their number carried privately-purchased shotguns or hunting rifles for which ammunition tended to be in short supply (Gabriel & Kermel 1988, 50-51). The FLNKS is not known to have conducted a general military training programme for its activists, whose only prior contact with military life usually consisted of time spent in French national service.

A select group of Kanaks commonly known as the stagiaires libyens (Libyan trainees) constituted the exception to this rule. In September and October 1984, seventeen activists received six weeks' training of an unspecified nature in Libya, as did nineteen three years later (Fraser 1988, 21). The total of thirty-five trainees involved form the only concrete evidence available of external support for FLNKS activism, which suggests that Libya was not as willing to challenge France in New Caledonia as it had been in Chad. There is no proof that foreign arms were procured by the FLNKS. The organisation's military arsenal was restricted to French weapons Kanak militants stole from rural gendarmeries.

Compared with the militants the FLNKS could muster, the forces of law and order in New Caledonia were substantial. By November 1984, 1300 gendarmes were present, who were reinforced by eight Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité (Republican Security Companies-CRS), a peculiarly French species of riot police, the following month . As potential back-up there were 1526 regular army troops stationed in the territory (Libération, 24-25 November 1984). Should numbers already present prove insufficient, reinforcements could swiftly be airlifted from metropolitan France and French Polynesia. In response to the greater tensions of the second FLNKS militant campaign from April 1988, by 1 May over 12,000 men under arms were deployed in New Caledonia, a total which included CRS, gendarmes and regular army troops but omitted the 150 members of Nouméa's municipal police. This figure was the equivalent of one man for every twelve civilians in the territory (Damoclès, April-May 1988).

Under the liberal-conservative government of Prime Minister Jacques Chirac, from 1986 to 1988, the French military countered rural Kanak activism through its policy of nomadisation. Army units were stationed near tribes, ostensibly to assist with rural development projects. Nomadisation was intended to impede any future FLNKS mobilisation both by winning over rural Melanesians and by monitoring Kanak activists (Maclellan 1990, 7). Should armed insurrection take place, rural camps were to serve as strongholds from which military operations could be conducted. The French State in the 1980s had at its disposal ample means to dominate New Caledonia militarily if faced with a local uprising, but rural pacification efforts were intended to lessen the likelihood of this eventuality.

The minority support base of the FLNKS and its slender military means limited the effectiveness of any resort it might have had to armed insurrection. The consequence of a generalised rebellion in 1984 or 1988 would have been reprisals from the French State which could have led to the FLNKS's destruction. To avoid this possibility, the formation employed low intensity violence that did not really live up to its image of a Kanak national liberation struggle.

The Active Boycott of 1984

On 18 November 1984 the FLNKS staged its active boycott of the first territorial elections held under the Lemoine Statute. Kanak voters were told to stay at home, and the FLNKS sought to dissuade French loyalists from turning out with roadblocks, pickets and the occupation of various rural polling stations. This disruption was not widespread enough to force the postponement of the elections, although the resultant abstention rate was 49.87 per cent (Le Monde, 20 November 1984). In the absence of an FLNKS vote, the RPCR largely swept the field, gaining thirty-four of forty-two seats in the Territorial Assembly, as the local parliament was then called. Of the Kanak parties, only LKS participated. It had six territorial councillors elected in the absence of any Kanak competition.

The election boycott marked the beginning of a period of civil disorder in New Caledonia which was to last into 1985. During this period, the FLNKS attempted to invoke feelings of insecurity among French loyalists in rural areas. It was hoped that if sufficiently unnerved, they would desert their properties and what had once been tribal lands would revert back to Melanesian ownership. FLNKS militants burnt down and ransacked isolated homesteads. To isolate rural centres, they set up roadblocks and cut telephone and electricity lines. At Thio, a mining centre on the east coast of the Grande Terre, seven roadblocks were adequate to cut off around 2000 inhabitants from 21 November to 10 December (Le Monde, 29 November 1984, 11 December 1984). In January 1985, a balance sheet of the effects of New Caledonia's troubles from 13 November to 31 December 1984 was compiled by the French High Commission in Nouméa - 107 roadblocks had been erected, both by French loyalists and by Kanaks; ninety-six buildings and cars had been set ablaze; forty-one properties had been vandalised and looted; fifteen bomb explosions had occurred and eighty-six firearms had been confiscated. Eighty-four people, including French loyalists as well as Kanaks, had been interrogated about these events, of whom forty-seven were placed on charges. Deaths in the same period totalled sixteen, all but four of whom were Kanak militants (Libération, 4-6 January 1985). By early 1985, over 2000 people had left the bush to seek security in Nouméa (Connell 1987, 344).

For their boycott, FLNKS militants used harassing tactics which entailed withdrawing and reforming concealed in the bush when met with overwhelming force. Gendarmes and CRS clearing roadblocks would be met with a hail of rocks or sometimes gunfire, but Kanak activists usually dispersed when charged. This occurred on 19 November 1984 at a roadblock near Hienghène, where one gendarme was wounded (NC, 21 November 1984). In some cases, as happened at Ouégoa on 30 November 1984, several hours later the same spot would be reoccupied and new roadblocks erected (Le Monde, 1 December 1984). Kanak methods drew on elements of traditional Melanesian warfare, where victory depended less on winning pitched battles than on gaining the upper hand through tactics of stealth and harassment which would force the adversary to negotiate mutually advantageous peace terms (Douglas 1990, 45-46).

On 1 December 1984 the FLNKS announced the establishment of the provisional government of Kanaky. The régime was a self-appointed one of dubious democratic legitimacy. Its claim to represent Kanaks was contested by LKS, which held that the government's foundation was a rash, provocative act. French loyalists decried the provisional government, with good reason, as an affront to the majority will of the territory's voters, who did not desire independence, still less independence led by the FLNKS.

The term provisional government had an imposing air. In reality this body was a skeletal structure unsuited for governing New Caledonia, even in the unlikely event that it found itself in that position. It was not until the second FLNKS congress at Nakéty on 9 February 1985 that the roles of the provisional government and its subordinate structures were defined in the most general terms (FLNKS 1987, 12-13). The FLNKS had embarked on its national liberation struggle with no detailed vision of what its Republic of Kanaky would be like, and had formulated neither social nor economic policies. The provisional government's president, Jean-Marie Tjibaou, the head of the UC, only belatedly responded to these policy deficiencies.

The provisional government nevertheless held the potential to force concessions from Paris. Its existence posed a considerable embarrassment for the French Socialist Government of Laurent Fabius, which was pilloried by the opposition for not dissolving the FLNKS as a threat to republican law and order. Vociferous remarks were pronounced by various liberal and conservative deputies in the French National Assembly. On 21 December 1984 a former French president, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, and six former French prime ministers - Jacques Chirac, Raymond Barre, Pierre Messmer, Maurice Couve de Murville, Jacques Chaban-Delmas and Michel Debré - issued a joint statement condemning Fabius's handling of New Caledonia (Le Monde, 23-24 December 1984). His government was accused of wishing to subvert the constitutional self-determination process and republican law generally in favour of Kanak nationalism, thus endangering France's presence in New Caledonia. During the final weeks of 1984, the FLNKS boycott brought New Caledonia to the forefront of political debate in Paris (Satineau 1987, passim.). Socialist leaders responded by reconsidering the Lemoine Statute. On 4 December, Fabius announced he would be assuming personal responsibility for the New Caledonian portfolio. Three days earlier President François Mitterrand had appointed Edgard Pisani, a Gaullist minister of agriculture in the early 1960s who had since joined the Socialists, as special government delegate to New Caledonia. His brief was to restore law and order and, within two months, to formulate proposals for further reforms which might pacify the FLNKS.

Possibilities for dialogue were nearly cut on 5 December 1984 when an ambush by French loyalists near Hienghène resulted in the death of ten FLNKS activists, including two of Tjibaou's brothers. FLNKS executive members resolved that the coalition would gain political stature by not retaliating (Rollat 1989, 219). Similar restraint was shown after the deaths near La Foa of Eloi Machoro, the FLNKS security minister, and his subordinate, Michel Nonnaro, on 12 January 1985. The official explanation was that gendarme snipers had intended to shoot to wound them, but poor marksmanship had resulted in their deaths. The FLNKS accused Pisani of having given express orders for the assassination of Machoro, who was well-known for having led the blockade of Thio. Pisani denied this, but did not rule out the possibility that the pair's deaths were intentional, as they were vilified by local gendarmes (Pisani 1992, 340-342). Pisani praised Tjibaou for his restraint, although the provisional president of Kanaky was probably not solely making a moral gesture. A realisation that the FLNKS provisional government was of an embryonic nature and was not prepared for civil war may have also played a part in Tjibaou's restraint.

1985-1987: Abandoned dialogue

During reform negotiations in December 1984 Pisani managed to calm tensions by convincing the FLNKS to dismantle its roadblocks. When faced with a rise in Kanak and loyalist protests against his proposals in January 1985 he declared a state of emergency. Although both French loyalists and Kanaks rejected the state of emergency as a punitive measure, it forced a moderation of tempers.

The eventual product of Pisani's time in New Caledonia was the Fabius Statute, promulgated in August 1985 (JO, 1985). The principal concessions the statute offered to the FLNKS were the granting of greater powers of self-administration to New Caledonia's regions, and the provision for a self-determination referendum in 1987. In a remarkable about face, the FLNKS approved the Fabius Statute, even though it manifestly failed to fulfil Kanak demands for an immediate, restricted self-determination vote. At its third congress, held at Hienghène from 25 to 26 May 1985, with some dissension from its minority members the FLNKS abandoned its boycott of territorial institutions and resolved to participate in forthcoming local elections. Tjibaou, leading the largest party within the FLNKS, saw the regional administrative powers offered by the new statute as a mechanism which would enhance Kanak rural autonomy as a preliminary step toward independence. A congressional motion declared "The region, through the engagement of militants in the field and during a transition phase [under the Fabius Statute], will assist in the construction of Kanak Socialist Independence and will concretize the claims of the Kanak People, which will have its own mobilisation as its only guarantee" (FLNKS 1987, 16). The Fabius Statute was pragmatically exploited for the developmental opportunities it offered. This cooperation undermined the credibility of the provisional government and indicated that the FLNKS was not entrenched in its opposition to French institutions (Clark 1987, 93).

FLNKS pragmatism gained it sixteen out of the forty-six seats in the territorial elections held on 29 September 1985. All but one of these seats were located outside the South Region of the Grande Terre, where the RPCR was dominant. Thanks to what the RPCR termed a Socialist gerrymander, the FLNKS gained majorities in three out of four regions, while receiving 28.54 per cent of votes cast in the territory; 20,545 out of 71,995 (NC, 2 October 1985). As a result, the FLNKS gained sixteen of the forty-six seats in the Territorial Congress. In addition, LKS won one seat, with 4597 votes, or 6.39 per cent of votes cast (NC, 2 October 1985). This level of support did not augur well for Kanak chances of gaining majority backing for independence in 1987. The RPCR received 37,147 votes; 51.60 per cent of votes cast. RPCR support formed the greater part of a solid loyalist majority which permitted anti-independence parties to win twenty-nine of the forty-six seats in the Territorial Congress (NC, 2 October 1985).

Following the appointment of the liberal-conservative Chirac Government in Paris after the French legislative elections of March 1986, the new Minister to Overseas Departments and Territories, Bernard Pons, oversaw the organisation of the self-determination referendum proposed by the Fabius Statute. In line with recommendations made by Pisani in 1985, and with the voting criteria for the self-determination referenda organised for Djibouti and the Comoros in the 1970s, the Chirac Government decided that all New Caledonians of voting age who had been resident three years or more could participate, an arrangement likely to result in a majority vote for continued ties with France. As had been the case in 1984, FLNKS calls to restrict the electorate in favour of a majority Kanak vote were rejected as unconstitutional.

From early 1987 the FLNKS remobilised for a peaceful boycott of the self-determination referendum. The provisional government, from which very little had been heard since 1985, was reactivated in February (FLNKS 1987, 44). FLNKS protests gained some media attention, but as its non-violent abstention was of a minority nature, it did not invalidate the self-determination vote (Clark 1988, passim.). On 13 September 1987, the referendum confirmed what had been expected; that a majority of New Caledonian voters preferred to stay French. Of the 58.04 per cent of eligible voters who turned out, 98.30 per cent preferred to remain in the Fifth Republic. The overall abstention rate was 41.96 per cent (Le Monde, 15 September 1987). Pons took the vote as endorsement for the abandonment of the Fabius Statute and proceeded to draw up what became known as the Pons Statute, which was promulgated in January 1988 (JO, 1988a). The Pons Statute was not remarkably different from its predecessor in terms of regional powers, although regional boundaries were redrawn to counteract the representational advantages offered to Kanaks in 1985.

The Active Boycott of 1988

By 1988 the FLNKS had again become disillusioned with non-violent methods and swung back to militancy. Its anti-referendum campaign appeared ephemeral compared with the concessions its earlier boycott had prompted from the Fabius Government. Pons regarded the question of independence as having been resolved once and for all by the referendum and implemented his new statute without paying any great attention to FLNKS grievances. As in September 1984, the FLNKS decided to foment disorder in an attempt to force a reconsideration of government policy in Paris. In spite of the fact that President Mitterrand's first term of office had not led to the fulfilment of Kanak demands, Tjibaou held out the prospect that Mitterrand's reelection and the return of a Socialist government would permit a reconsideration of the question of self-determination. Tjibaou wrote an open letter to Mitterrand in March 1988 expressing the hope that the presidential candidate would be reelected "I hope that you will be able to return in force at the head of the [French] State in order to offer to our people [the Kanak people], and to France, of course, a new era of liberty" (Rollat 1989, 251, Le Monde, 2 April 1988). This stance stood in marked contrast with the repudiation of the Socialists announced by the FLNKS charter in 1984. There were indications that Mitterrand was sympathetic. He had denounced the reforms of the Chirac Government as unnecessarily divisive, and looked forward to the possibility of a reconciliation with the FLNKS (Le Monde, 25 February 1988, 29 March 1988).

The seventh FLNKS congress, held at Tibarama on 20 February 1988, resolved to organise an active boycott to disrupt the first territorial elections to be held under the Pons Statute. The elections were scheduled to coincide with the first round of the French presidential elections on 24 April 1988. The member party which advocated a more militant line was the UC. Other FLNKS members questioned the appropriateness of an active boycott. Doubts existed over whether the struggle committees were equal to the task, and it was feared that militant action might provoke a violent reaction from French loyalists and the forces of law and order (Gabriel & Kermel 1988, 144). As had occurred in 1985 when the FLNKS shelved its militancy to cooperate under the Fabius Statute, in 1988 Tjibaou used the UC's majority following in the formation to push a new line. He apocalyptically presented the boycott to the Front's militants as the last ditch chance for the Kanak people, claiming it entailed "resistance to the undertaking to eliminate the Kanak people. The [FLNKS] mobilisation will be forceful in order to check the elections and the installation of the Pons Statute" (Rollat 1989, 252, Le Monde, 23 February 1988). Tjibaou absolved the FLNKS in advance of any responsibility for what was to occur, blaming the Chirac Government for placing Kanaks in a position where violence seemed the only choice - "The government alone will be responsible for the uncontrollable sliding which is going to occur. There will perhaps be more blood spilt" (Rollat 1989, 252, Le Monde, 23 February 1988). While Tjibaou expressed the hope of reconciliation to Mitterrand, the FLNKS was preparing for confrontation with the French State.

As in November 1984, the boycott failed to prevent the elections from taking place, forcing the closure of just thirty-one of the 139 polling stations in New Caledonia (PIM, June 1988). On the Grande Terre, scattered roadblocks were erected, and there were stand-offs between Kanaks and gendarmes, but the generalised disruption predicted by Tjibaou did not eventuate.

In the Loyalty Islands too the boycott fell short of expectations. Militants on Ouvéa, Lifou and Maré were originally intended to go into action simultaneously but in the event only the Ouvéa struggle committee mobilised (Rollat 1989, 252-253, 261). On 22 April, its members occupied the gendarmerie at Fayaoué, killing four gendarmes in the process. The post's arsenal was seized, and surviving personnel were taken hostage. These hostages were split into two groups, of which one's members were soon released. The fate of the other group, held by militants led by Alphonse Dianou, the head of the UC youth section, became the central issue of a hostage incident. Dispelling any uncertainty, the FLNKS claimed responsibility for the Fayaoué abductions with a statement issued by its political bureau on 24 April - "What has taken place on Ouvéa is not an isolated action by several extremists or uncontrolled terrorists. It consists on the contrary of a unitary action inscribing itself in the framework of the checking of the Pons Statute decided by the seventh congress of the FLNKS at Tibarama" (cited in Gabriel & Kermel 1988, 149).

The RPCR responded by calling for the dissolution of the FLNKS as a terrorist organisation, but Prime Minister Chirac refrained from taking this step. An assault took place after the failure of extended negotiations with Dianou and the FLNKS executive for the release of the hostages. With Mitterrand's assent, on 4 May French troops stormed the grotto where twenty-three captives were still being held. As he was commander-in-chief of the armed forces, President Mitterrand's approval was required for the operation, and had been given on 3 May. Mitterrand stated in an interview a year later that concern for the safety of the hostages was the principal reason for his assent to Chirac's request. Mitterrand downplayed speculation in 1988 that the assault was a ploy by Chirac to attract votes in the second round of the French presidential elections on 8 May, which consisted of a run-off between Mitterrand and Chirac. Mitterrand commented "this fantasia perhaps cost me half a point" (Favier & Martin-Roland 1991, 749). Even assuming the Ouvéa assault was an electoral ploy by Chirac, it failed to tip the electoral balance in his favour Mitterrand was reelected president for another seven years, with 52.06 per cent of national votes cast (Cole & Campbell 1989, 151).

In total twenty-five men, including nineteen Kanak activists, died in the troubles on Ouvéa. Controversy followed over whether the assault was justified, and whether excessive force had been used. An official inquiry concluded that four Kanak activists captured by French forces died either of maltreatment or neglect at the hands of their captors (Legorjus 1990, Plenel & Rollat 1988, passim.).

The Matignon Accords

After these troubles the FLNKS reassessed the utility of maintaining its boycott. The balance sheet of its actions was a death toll that was likely to rise should violent protest continue. Another frustration for the FLNKS executive was that the boycott had exposed certain internal organisational problems. The Front's inability to achieve a full mobilisation of its struggle committees demonstrated both their ill-preparedness, and the unwillingness of certain activists to push confrontation with the French State to the extent that the Ouvéa struggle committee did. As in 1984, the FLNKS was faced with the superior military strength of French forces. The Ouvéa incident displayed again that although Kanak harassment tactics could inconvenience the French Government, if it came to armed confrontation, the French military had superior firepower. Independence via armed insurrection was not a viable option.

The FLNKS boycott of 1988 nevertheless brought about a reconsideration of the New Caledonian portfolio in Paris. The French Socialist leader Michel Rocard described the territory as the most pressing problem which faced him upon his appointment as prime minister in May 1988, and a reconciliation with the FLNKS and the RPCR was to be the first major achievement of his period in office. In May 1988 Rocard dispatched mediators to New Caledonia who opened discussions concerning the territory's future. The delegation found that both French loyalists and Kanaks were reconsidering their previous differences. Tjibaou recognised that Kanak militancy was not achieving results that would justify the continued loss of lives and decided to negotiate with Paris. Previously the RPCR had dismissed the FLNKS as a clique of terrorists, and had denounced past Socialist Governments for pandering to Kanak interests. This time it decided to negotiate both with the FLNKS and the Socialist administration led by Rocard. Jacques Lafleur, the RPCR president, wished to discourage any further violence before it spiralled out of control and was mindful of the fact that with five years of Socialist administration ahead, it would be in the better interests of New Caledonian loyalists to establish dialogue with Paris.

In June 1988 the FLNKS discarded its active boycott to participate in territorial institutions. Tjibaou chose to negotiate a settlement with the Rocard Government which led to the signature of the Matignon Accords, signed in Paris on 26 June and 20 August 1988. Cosignatories to the accords along with Rocard were delegations from the FLNKS, the RPCR, and LKS. The accords themselves consisted of a ten-year development agreement which established conditions for another New Caledonian self-determination referendum, to be held in 1998.

The Matignon Accords were the first, and critics would say the only, major success of Rocard's administration. In persuading New Caledonian loyalists and Kanaks not only to negotiate, but to sign, a document which would establish the basis for the territory's future, Rocard obtained what previous French governments had not. The three territorial statutes which had been adopted from 1984 to 1988 had all foundered on the absence of united New Caledonian support for the various measures imposed by Paris.

As he had in 1985, Tjibaou hoped to use the various development provisions under the new territorial administrative framework to build the infrastructures necessary for the foundation of Kanak independence. Despite having neither the military means nor the electoral numbers to force sovereignty from France, after non-violent protest and lobbying had failed to invoke a satisfactory response, the FLNKS managed to employ militancy in 1984 and 1988 to obtain concessions from Socialist Governments which partially met its demands.

The accords' development arrangements were designed to improve New Caledonia's general economic health and the lot of local Melanesians in particular. From July 1988 to July 1989, Paris received direct rule over New Caledonia while institutions outlined under the Matignon Accords were established. New Caledonia's Territorial Congress was stripped of its powers and the High Commissioner, Paris's representative in Nouméa, assumed executive control.

Acceptance of the Matignon Accords was put to the test in a national referendum on 6 November 1988. In having the accords adopted via referendum rather than by tabling them as a bill before Parliament, Rocard aimed to avoid the prolonged parliamentary debate and opposition filibustering that previous Socialist reforms for New Caledonia had encountered. These delays would have been repeated given the relative Socialist majority in the National Assembly from May 1988 and the dominance of opposition parties in the Senate. Rocard also endeavoured through a direct consultation with all French voters to give the accords greater democratic legitimacy. That legitimacy was undermined by a poor response to the referendum. Amid national indifference to events in New Caledonia, 36.92 per cent of eligible voters went to the polls; the lowest participation rate for any referendum held under the Fifth Republic (Le Monde, 10 November 1988). Of those who participated, 70.47 per cent lodged their acceptance of the Matignon Accords, a group representing only 26.02 per cent of French voters. In New Caledonia, polling was higher and the results there showed evidence of substantial opposition to the Accords. 63.24 per cent of eligible voters there participated, of whom 52.38 per cent deposited votes for the Accords (Le Monde, 10 November 1988). Even though its affirmation was weak, the referendum endorsed the Matignon Accords, which duly became law (JO 1988b).

Although intended by Rocard to promote greater self-government in New Caledonia (Rocard 1989, 72-85), in some respects the Matignon Accords instituted centralisation. The High Commissioner became the head of the territory, a position held by an elected territorial president under the previous statute. Some greater powers were granted to the territory, but the High Commissioner retained considerable authority. His wide range of responsibilities include foreign relations, immigration, defence, law and order, natural resources, currency, civil and commercial law, state administration, most of the education system and the guidance of land reform.

In essence, territorial administrative powers were not greatly changed by the Matignon Accords. As it has since the Fabius Statute, the Territorial Congress acts as the local parliament. This has to be consulted, but not necessarily heeded, by Paris over legislative proposals affecting New Caledonia. Although New Caledonia's four existing regions were dissolved and three new provinces were drawn up, the powers of the former and the latter were similar. The provinces are charged with the maintenance of their public facilities, administrative personnel, aspects of primary and secondary schooling, vocational training, urban planning and housing, local investment, health services, some tax levies, sport and cultural activities, land and tribal law, agriculture, livestock, hunting, forestry and fisheries (High Commission 1992, 7).

Nevertheless the Matignon Accords featured certain innovations. To encourage rural development in the predominantly Melanesian North Province and Loyalty Islands Province, new territorial budgetary arrangements provided favourable annual funding allowances for them. Of provincial recurrent expenditure allowances, 50 per cent is allocated to the South, 18 per cent to the Loyalties, and 32 per cent to the North (High Commission 1992, 11). Of capital expenditure allowances, 40 per cent goes to the North, 20 per cent to the Loyalties, and 40 per cent to the South (High Commission 1992, 11). On a per capita basis, these arrangements are advantageous to the North and Loyalties. Furthermore the accords installed state-provincial development contracts weighted to the advantage of the North and the Loyalties. From 1990 to 1992, 50.7 per cent of development contract funding went to the North, 18.3 per cent to the Loyalties, and 31.0 per cent to the South (High Commission, 33). These contracts established direct provincial links with Paris so that funds would not have to pass through the territorial administration, which was under the majority control of the conservative RPCR.

Another major change concerned electoral reform. The boycott of the

territorial elections in April 1988 left the FLNKS without representation in

the Territorial Congress. Consequently the signatories to the Matignon Accords

agreed that elections would be held under the new provincial structure in June

1989. These elections reaffirmed the conservative majority in New Caledonia,

with anti-independence parties gaining thirty-two of fifty-four seats. Of those

thirty-two seats, twenty-seven were held by the RPCR, three by the Front

National (National Front-FN), and two by a group of FN dissenters, Calédonie

Demain (Caledonia Tomorrow). Even though the FLNKS's status as a minority

electoral grouping in New Caledonia was reconfirmed, it obtained absolute

majorities in the Loyalty Islands, with four out of seven seats, and in the

North, with eleven out of fifteen seats. LKS gained one seat in the Loyalties.

(NC, 12 June 1989.)

Kanak Development under the Accords

Apart from disillusionment with the shortcomings of militant activism, the FLNKS signed the Matignon Accords because they offered avenues for Kanak development. Since 1985 the formation had been aware of the handicaps of attempting to found a sovereign nation-state with a largely rural, tribal support base in a territory where non-Melanesian immigrants dominate the cash economy. As was the case under the Fabius Statute, the FLNKS's strategy is to employ state development funding to improve the socio-economic standing of areas administered by Kanaks. Such activity will, the theory goes, endow Kanaks with the infrastructure upon which to found the Republic of Kanaky. This strategy's drawback is the inherently dependent position in which it places the FLNKS with regard to the French State. As Kanak development under the accords relies on Parisian funds and expertise, the trend has been to strengthen, rather than to sever, links between the Kanak hinterland and France.

The wave of construction undertaken in the North and the Loyalties since 1989-roads, schools, hospitals, hotels, telecommunications, electrification, port facilities-has enabled improved integration with, and also increased reliance on, the South. Paul Néaoutyine, the FLNKS president, commented ruefully on how the bulk of rural construction work is completed by Nouméan firms, as nearly all the available contractors are based there (Le Monde, 23 May 1991, 17 October 1991). The development funds paid to these firms are transferred to the South rather than circulating in the rural economy.

The lack of skilled labour in the North and the Loyalties stems from the low success rate of indigenous Melanesians in the French education system. By 1989, 0.5 per cent of New Caledonia's Melanesians had obtained tertiary level education, compared with 10.8 per cent of the local European population (INSEE 1989, 40), which in itself constitutes a low figure by metropolitan French standards. The Matignon Accords aim to counteract this inequality through increased funding for all levels of education, and by offering Melanesians greater access opportunities to higher learning. FLNKS leaders are well aware of this problem and have allocated large segments of their provincial budgets to education. The Loyalties allocated 42.11 per cent of its 1993 provincial budget to education (CL, January 1993). A major project set up by the accords is the 400 managers programme, designed to permit 400 young New Caledonians to receive professional training in metropolitan France by 1998. From 1989 to 1991, 75.4 per cent of the young people on this programme were Melanesian (High Commission, 22).

Perhaps unavoidably, young Melanesians are being inculcated with French values through the state education system. In the 1980s at least one French Socialist minister heralded the passing of the French republican ideal of cultural integration. In 1982 Henri Emmanuelli, then Secretary of State to the Overseas Departments and Territories, stated "Nowadays the old idea of integrating natives, dear to the republican ideal, is outmoded" (Emmanuelli 1982, 9). But the concept has displayed considerable resilience by becoming an integral part of the Matignon Accords. Kanak attempts at promoting indigenous values through education have not been particularly successful. In 1985 the FLNKS reacted against the French socialisation of Melanesian youth by setting up the independent Kanak Popular Schools. This was to be a territorial network which would teach traditional culture, thus allowing Kanak youth a greater understanding of its heritage. For want of funds and trained personnel, the schools declined in number to just five by the early 1990s, leaving most Kanak children reliant on French education. The accords have permitted the provinces to assume some control of local education, allowing the North and the Loyalties to promote the use of indigenous languages in primary school curricula, but from secondary level French remains the main language of instruction. In education, as in administration, law, medicine and other fields of professional endeavour, Kanak social advancement under the Matignon Accords lies through the acceptance and mastery of European systems.

With major investments in nickel mining and tourism, the North and the Loyalties have advanced Kanak participation in the territory's cash economy. Traditional Melanesian economic values, centred on tribal subsistence and collective ownership, with barter as the basis for exchange, fail to offer a strong commercial basis on which to build independence. The North has invested in tourism to the extent of purchasing two hotels and a casino in Nouméa, and has authorised the creation of a Club Med resort at Hienghène. In April 1990, with state assistance the North purchased a mining company from Lafleur. At Canala, a local initiative has led to the reopening of closed works and the creation of the Kanak Mining Company, employing sixty locals (Le Monde, 3 February 1993).

Large-scale Kanak investment in mining and high-prestige tourism operations follows well-established patterns of French commercial initiative. As has been argued by the Australian Council for Overseas Aid (1990, passim.), micro-scale investment at tribal level has no such precedent and is more problematic. Whether the implementation of the Matignon Accords can effect change at tribal level to the satisfaction of traditional values has yet to be proven. Rural Melanesians now have better access to roads, schools, hospitals, electricity and running water thanks to public works projects financed under the accords, but questions surround the future status of these people. The major issue is the extent to which the tribal milieu should become westernised in order to conform to French development models promoted to a degree by the FLNKS. Richard Kaloi, the FLNKS President of the Loyalty Islands Province, has asserted that Kanak development lies through the amalgamation of traditional Melanesian and modern European values (CL, September 1992), but their contrasting philosophies do not necessarily mix well. Land reform is symptomatic of differing cultural perceptions between French and Kanak administrators and tribal elders. The French State prefers that private and public land be ceded to Melanesians for cash cropping. This view is at odds with the tribal perception of land as a source of clan prestige regardless of that land's state of cultivation.

Employment is another area where French and Melanesian values clash. State officials wish to see more Melanesians in paid employment so that they might attain similar living standards to those of Europeans. In 1989 the unemployment rate in the Loyalties was 36 per cent, compared with 21 per cent in the North and 12 per cent in the South, figures which reflect the number of rural Melanesians still living largely outside the cash economy (High Commission 1992, 17). This situation was presented by the High Commission as a "pressing challenge" which needed to be addressed (1992, 17). However whether Melanesians living in tribes are really unemployed depends on your cultural values. Those not in full-time paid employment contribute to tribal subsistence economies. Is it preferable that these societies should be further eroded by western values of individual achievement, private ownership and profit? Conversely, should New Caledonia's tribal population experience a materially impoverished existence while the territory's urbanised population enjoys a modern, consumer lifestyle? These questions are not merely rhetorical, but lie at the heart of the developmental choices facing FLNKS leaders in the 1990s.

Kanak Integration or Independence?

Increased Kanak integration with France under the Matignon Accords has not gone unnoticed among Kanaks. Certain among them see this trend as a dangerous threat to prospects for Kanak independence. The most violent expression of Kanak opposition to the FLNKS's signature of the accords came in May 1989. Tjibaou and the FLNKS vice-president, Yeiwené Yeiwené, were assassinated on Ouvéa. Djubelli Wea, the Kanak responsible for their deaths, was a prominent Ouvéan activist who felt that Tjibaou had surrendered to the French by signing the accords (Tristan 1990, passim.). Unconfirmed rumours spread in the FLNKS that FULK, a minor component of the FLNKS, was in some way responsible for the assassination. FULK never signed the accords, believing that negotiating with Paris endangered Kanak sovereignty. FULK has repeatedly berated the rest of the FLNKS for its cooperation with Paris and the RPCR. Since 1988 the party has drifted away from the FLNKS. In January 1992, FULK renamed itself Congrès Populaire (Popular Congress), and advanced a policy platform of broad opposition to the accords (PNB, August 1992). In April 1991 LKS withdrew from the Matignon Accords, claiming that the agreement was leading Kanaks away from independence (Le Monde, 12 April 1991). It later revised this stance, and in December 1993 attended a meeting in Paris of the coordinating committee overseeing the accords (CM, December 1993). Such dissent has not broken FLNKS adherence to the accords; support which has been maintained in spite of minority Kanak criticisms from within and outside its ranks.

The RPCR signed the Matignon Accords because in addition to restoring civil order, the accords' development possibilities might lead Kanaks to realise that their welfare would be better served by remaining French rather than facing the uncertainties of independence. The RPCR sees the accords as the route to further Melanesian integration with the Fifth Republic, and to the eventual abandonment of Kanak nationalism. The FLNKS did not take up Lafleur's offers to redefine the accords and drop self-determination, but he was still confident that come 1998 a majority of New Caledonian voters will reaffirm their willingness to stay French.